The U.S.-China trade war isn’t the death knell for globalization

September 24, 2019

Jean-Pierre Couture

For several months, the financial markets have been bouncing up and down in response to news reports on the trade tensions between China and the United States. Uncertainty looms as investors’ eyes are riveted on President Trump’s tweets and Beijing’s response. Our Chief Economist offers an overview of the geopolitical “sujet du jour” and his reading of the various economic scenarios.

Globalization 101: Is the United States shooting itself in the foot?

Globalization is based on the concept of the competitive advantage of nations. Some countries have a natural resource endowment, whereas others have a skilled workforce, outstanding transportation infrastructure or a significant technological advantage. In recent decades, advances in telecommunications and logistics have allowed companies to relocate their operations and optimize their production of goods according to the competitive advantage of nations, a shift that has accelerated globalization and economic integration.

The concept of the competitive advantage of nations is that if country A has a large, cheap workforce, it will attract labour-intensive industries and eventually get richer. A company based in country B, where labour is scarcer and more expensive, will benefit from having its products assembled in country A. Thus the competitiveness of the companies in country B is largely influenced by the fluidity of trade with its trading partners. Companies in a country turned in on itself will be unable to compete with foreign multinationals or benefit from the growth of foreign markets. Foreign firms will clearly have an advantage over those in the country with the closed economy.

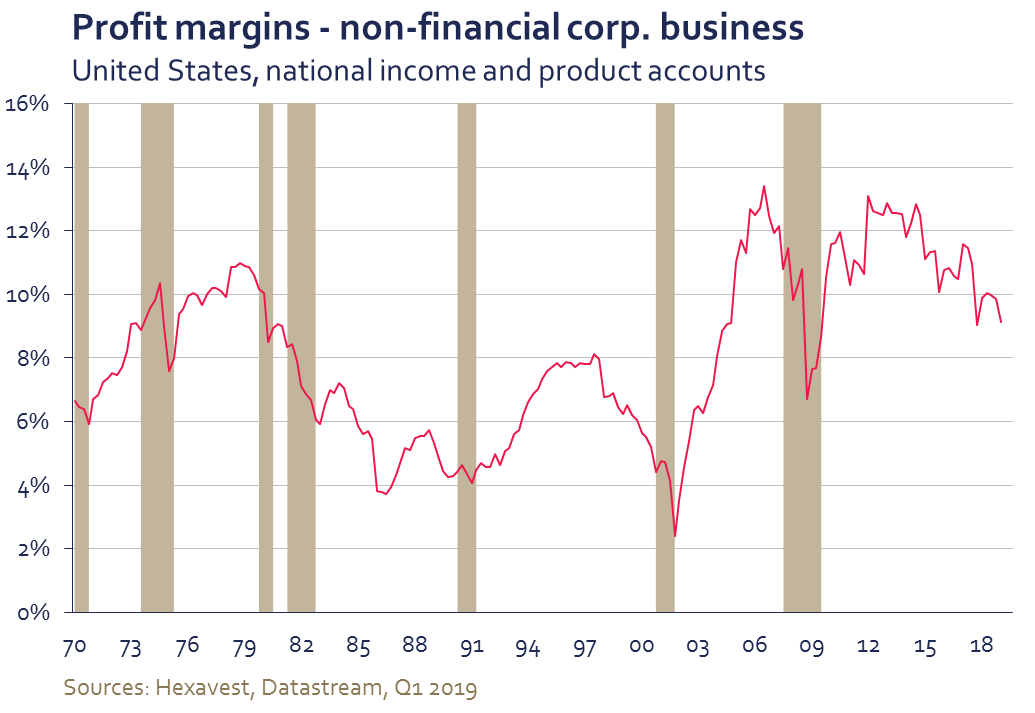

In our view, this is the situation in which U.S. companies could find themselves. Their own government is weakening their competitiveness and profitability by imposing tariffs on imported inputs and is jeopardizing their international expansion, notably by undermining their relationship with growth markets. In these conditions, it would not be surprising to see the profit margins of U.S. non-financial companies continue to erode over the next few years (see chart below).

Beyond tariffs

What will U.S. companies do if they, like their foreign competitors, want to benefit from Asian growth and the competitive advantages of other nations? The American Chambers of Commerce in Beijing and Shanghai recently surveyed 239 U.S. firms and found that 35% of them think they need to increase their investments in China. There has also been a sharp increase in direct investment in China’s neighbours, especially Vietnam. In fact, we think they have no choice but to increase their presence in the region: current and future growth is in emerging Asia, not in the mature economies. The tariffs imposed by the U.S. government are an obstacle, but they are far from the only variable that will influence business investment decisions.

“While tariffs are important, they are only one of the many factors companies have to consider when locating production:

others include the quality of employees, cost of logistics, local content requirements and the scale of different markets.

And for products with hundreds of different components, analyzing the impact of tariffs is in fact quite complicated.”

– Lance Noble, How Multinationals Are Managing The Trade War, Gavekal Dragonomics, June 4 , 2019

To take advantage of foreign growth, multinationals must not only have access to these markets, but their rights must be respected once they can sell their products and services there. If their patents are not protected and the government of the target market protects local industries excessively, then the playing field will not be level.

China has changed a great deal in 20 years

The economic strategy of the Chinese state has long been to provide jobs for the millions of workers who have flocked to the cities. Full employment has been the best way for the Communist Party to maintain social peace. Protecting local firms and state-owned enterprises from international competition therefore seemed fully justified. Today, however, China is less confronted with this demographic problem now that the labour force is shrinking.

The Party's new goal is to have China integrated into the production chain, to produce more high-value-added goods (Huawei and ZTE being prime examples) and to move away gradually from labour-intensive industries (many Chinese companies are shifting their production to neighbouring countries to benefit from a more abundant and cheaper workforce). At the same time, however, China wants to continue to enjoy the benefits of its “developing country” status within the World Trade Organization (WTO). This status allows it to continue to protect certain sectors from foreign competition.

Certainly, developed countries were down on their knees before China in 2001, eager to see it join the WTO so that they could take advantage of its huge market. Almost 20 years later, the context is much different. China’s economy has changed dramatically since it joined the WTO. Now that it is more mature, with its own national brands and global leaders, we think it is high time for the government to open the borders to foreign firms and to protect them from counterfeiting and theft of intellectual property.

Time may not be on the Trump administration’s side

The Trump administration has chosen a hard-line approach, but time might be working against it. First, the current chaos is holding the U.S. economy back. Uncertainty is undermining the business climate everywhere, even in the United States. U.S. companies are postponing investment because of a lack of visibility over their supply chains and export markets. But business investment, not consumption, dictates the pace of recessions. In addition, there will be an election in the United States in 2020, which is obviously not the case in China. Popular support for the Trump administration’s approach is likely to fade as the U.S. economy slows.

The end of globalization?

Regardless of the outcome of the trade war, we don’t think it will bring an end to globalization. The United States has excluded itself from the group of predictable trading partners, and the outcome will be a reorganization of trade flows. The Trump administration has also sabotaged its trade relations with Canada, Mexico and Europe and has excluded itself from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, sowing disorder in the supply chains of U.S. companies. The United States may be a large market with nearly 20% of global GDP, but growth is elsewhere.

The emerging Asian economy – with 60% of the world’s population – is the same size as the U.S. economy but is growing two to three times faster. Trade between emerging countries is expanding structurally at a rapid pace. The latest data show a rebound in trade between countries in the region as it declines in the rest of the world. European, Japanese, Korean and Chinese multinationals have a much greater presence in the region than their U.S. competitors. They should therefore benefit more from low production costs and regional growth. Western investors who always make the United States the centrepiece of their reasoning may fail to see what is going on in Asia and miss the boat.

All that being said, the Western countries have tolerated China’s unfair trade practices for too long. Sooner or later, China will have to open its borders and ensure the rights of foreign firms are respected. The country is on the right track, but the pace of change is slow.

Can the U.S.-China trade war be resolved?

Of course, several scenarios are possible, including a trade truce rather than an agreement. In such a scenario, the current tariffs would remain in place, but there would be no further escalation. Another possible scenario is that the two countries may be forced to reach an agreement. A recession caused by the current uncertainty, with a drop in investment and significant job losses, could force the leaders to restore business confidence by providing more visibility over global trade. Let’s not forget that the Chinese Communist Party must always maintain full employment and that the Trump administration hopes to be re-elected in 2020.

Finally, there are disaster scenarios that we consider less likely: escalating tariffs and threats, boycotts, military tensions and so on. We think corporate lobbyists are working feverishly with their governments to avoid such scenarios and to make them listen to reason. In our view, the trade-truce scenario or an agreement forced by an economic downturn are the most likely outcomes.

“Our members are in China for the long term. None of them are anticipating orders to leave.”

- Craig Allen, president of the US-China Business Council, August 29, 2019

Source of all data and information: Hexavest as at August 31, 2019, unless otherwise specified.

The returns of the MSCI indices are presented net of deductions from foreign withholding taxes.

MSCI data presented may not be reproduced or used for any other purpose. MSCI provides no warranties, has not prepared or approved this report, and have no liability hereunder. Past performance does not predict future results.

This material is presented for informational and illustrative purposes only. It is meant to provide an example of Hexavest’s investment management capabilities and should not be construed as investment advice or as a recommendation to purchase or sell securities or to adopt any particular investment strategy. Any investment views and market opinions expressed are subject to change at any time without notice. This document should not be construed or used as a solicitation or offering of units of any fund or other security in any jurisdiction.

The opinions expressed in this document represent the current, good-faith views of Hexavest at the time of publication and are provided for limited purposes, are not definitive investment advice, and should not be relied on as such. The information presented herein has been developed internally and/or obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, Hexavest does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of such information. Predictions, opinions, and other information contained herein are subject to change continually and without notice and may no longer be true after the date indicated. Hexavest disclaims responsibility for updating such views, analyses or other information. Different views may be expressed based on different investment styles, objectives, opinions or philosophies. It should not be assumed that any investments in securities, companies, countries, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable. It should not be assumed that any investor will have an investment experience similar to any portfolio characteristics or returns shown. This material may contain statements that are not historical facts (i.e., forward-looking statements). Any forward-looking statements speak only as of the date they are made, and Hexavest assumes no duty to and does not undertake to update forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks, and uncertainties, which change over time. Future results may differ significantly from those stated in forward-looking statements, depending on factors such as changes in securities or financial markets or general economic conditions. Not all of Hexavest’s recommendations have been or will be profitable.

This material is for the benefit of persons whom Hexavest reasonably believes it is permitted to communicate to and should not be reproduced, distributed or forwarded to any other person without the written consent of Hexavest. It is not addressed to any other person and may not be used by them for any purpose whatsoever. It expresses no views as to the suitability of the investments described herein to the individual circumstances of any recipient or otherwise.